Arturo,

Your comment about the grim mood of some of our stories reminded me that we never discussed Marrareth. I myself have never had much use for tales in which the misfortunes of others are meant to be a source of delight but many do enjoy such laughable mishaps. Children in Geldorad have grown up laughing and singing about the trials of Marrareth for hundreds of years. I am interested to know whether children in Seven Hills will find these stories as fascinating as we seem to, so I have recorded three examples which are typical of the cycle.

Marrareth and the Knight Derimac

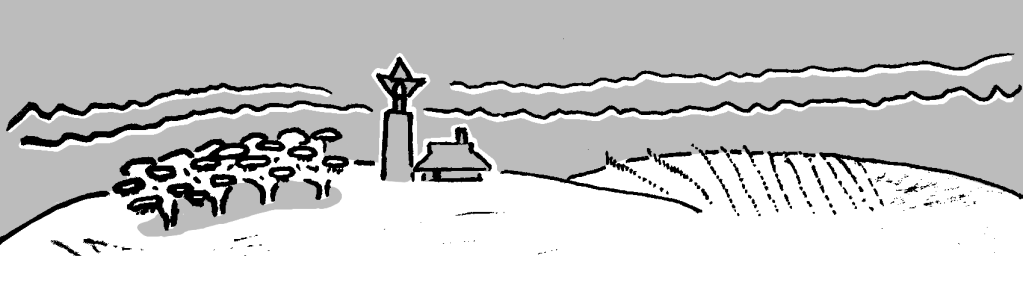

A lonely land borders the northern woods between the towns of Issodel and Pannadem. It is there that Whispering Weir stands. The river Hugwin issues out from the woods there and flows into the lands surrounding Geldorad. Were Whispering Weir ever taken by weald-wights or woodwose hordes, half the valley might be flooded or dried up.

Because that lonely land is so important, it is managed not by Issodel nor by Pannadem but by the grey city itself. Aldermen assign its caretakers. In the year 2649 they chose a young woman named Marrareth. She was the only one the aldermen could find to guard the Whispering Weir in the time after the Ruckus.

So she lived in a dark old cottage of only one floor. It was comfortable but unremarkable. Its only striking feature was the bell tower which housed a bell weighing over a ton. If ever the Whispering Weir were overrun by men or beasts, Marrareth was to ring the bell and call for aid.

Work was hard in the lonely land. Not only were there crops to tend to – pulse and nettles and quince trees – but she also had to forge her own tools, repair the cottage, and fight off whatever foes came prowling around the weir. She was brave and strong enough for all these tasks but she yearned for someone to help her. She wrote often to the aldermen in the city, pleading for them to send a helper. But every time they wrote back and said there was no one to send.

One cloudy day she was tending the lentil fields when she saw a man strolling up from the south. He was a tall young knight with dark eyes and gentle features. He was strong and swift and clad with studded leather armour and a bright silver helmet.

He hailed Marrareth and said, “I knew not that any soul so fair lived in this lonely land. I’ve heard only of brutes and savages. My name is Derimac, knight-in-training.”

“I am Marrareth,” she replied after a pause, bowing when her manners caught up to her. “What brings you here, Derimac?”

He answered, “I come to ply my trade and win renown. Every knight must face perils of the wilderness before earning their place among the city’s champions. Wherever there is danger, there is my home.”

“There’s dangers enough here,” said Marrareth. “I fought off a pack of wolves just last night and struck down a banshee just this morning.”

“Then this is just the place for me!” said the knight with a smile. “Valiant Marrareth, let me stay here and fight in this land and I shall repay you by labouring in your fields.”

This was more than Marrareth had ever hoped for. Derimac was strong and handsome and courteous above all. He stayed with her for two weeks, sleeping inside the bell tower at night and fighting or labouring through the day.

Marrareth was expected to write a report for the aldermen at the close of each month. She wrote to them of the harvests, the weather, and the movements of forest beasts but she said nothing of the young knight Derimac. After all, if they knew she at last had help (and such keen and kindly help at that) they would send her no other. She hoped that her workload would become even lighter.

And she feared that she could not rely on the young knight forever. She feared that one day he might leave.

“Will you return to the city?” Marrareth asked one day as they watched evening light dance over the weir.

He answered, “Not unless my renown reaches them from here. Then they may consider me worthy to number among the champions and they will send for me. But even then I may wish to remain longer to hone my skills. There is still much I could learn from you, Marrareth.”

Derimac was kind and courteous but always a little distant. He lavished Marrareth with praise but feared to stand or sit too close to her. So Marrareth thought she would embolden him with praise of her own and perhaps open the young knight’s heart. She praised him for banishing ghosts, harrying wolves, and even cleaning the cottage. As she planned, Derimac grew bolder and she sometimes even caught him staring at her.

Now with her workload so much lighter Marrareth was free to travel four miles west to her neighbour Annesse who watched the neighbouring shire. Annesse was an old widow whose late husband left her some wealth. She often hired help from nearby hamlets when her work grew too difficult, so there was no bitterness or envy from Annesse when Marrareth told her,

“Aunt Annesse, I have met the most wonderful knight! He is handsome and humble and brave and strong! Who would have thought such a rugged man would be the one to make my life easier?”

“That is wonderful, Marrareth!” said Annesse. “And what is the name of this wonderful man? I suspect I will have to get use to hearing it!”

“Derimac!” she answered with a wistful sigh. “Such a noble name for such a noble knight!”

“Derimac!” Annesse repeated. “That is a fine name! I can’t wait to meet him!”

Annesse was a careful woman. She told only one of her friends about Marrareth’s fortune, and she was also a careful woman. That careful friend only told one of her relatives, a careful man who told the tale only to his most careful colleague. As was bound to happen, the renown of Derimac followed a careful trail back to the city aldermen who immediately declared the young knight worthy to sit with the city champions.

And Derimac, emboldened by Marrareth’s constant praise, felt worthy of joining them.

He kissed her hand before leaving, offering an unlikely promise that some day he would visit her. On a cloudy afternoon in the lentil fields, three weeks after they met, they parted ways.

Marrareth tied up her hair, sharpened her tools, and after a gruelling evening of weeding she retired to her cottage and wrote a letter to the aldermen, asking if they found anyone to send to help her.

Marrareth and the Half-Whorven Borister

In a lonely land by the Whispering Weir lived Marrareth. She lived in a small dark cottage by a tall dark tower, and up the tower was a bell which she was to ring if ever weald-wights or woodwoses overran the Whispering Weir. She lived there alone, farming the fields and watching the woods and always hoping for a helper to come and lighten her lonely labours.

Marrareth ate well, as should anyone so hardworking and strong. Every other month she bought a barrel of marchman’s meal which is tripe and other offal smoked and dried and salted and pounded into powder. She bought it at a fair price but had to raise crops of her own to sell for it. She grew quinces and nettles for nourishment and groundnuts and rapeseed for their oil.

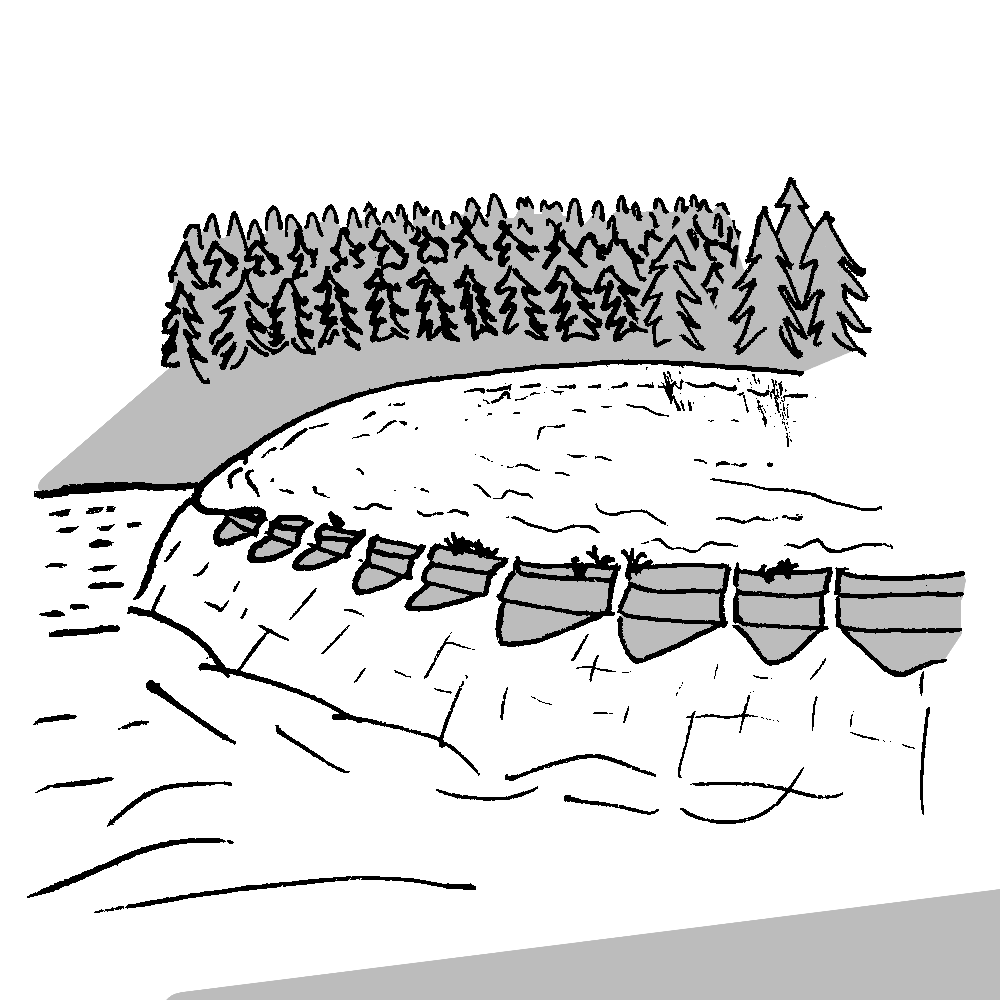

She had to tend to her crops with great care. Not only did she have to watch out for all the pests and blights which any farmer fears, but if ever the roots of her crops touched the roots of the weald they would become sickly and tainted and deadly. They would become whorven. If a grub ate a whorven leaf it grew into a whorven moth. If a spider ate a whorven moth it became a whorven spider and made a bird whorven in turn. And a whorven wolf or bear is more than a dozen brave men can face.

But Marrareth could face a dozen whorven rabbits as she proved late one evening when she smote half of them and sent the rest running. They took down ten of Marrareth’s quince trees but paid a dear price for it.

She thought to herself, “If I had a good helper I might not have lost a single one. I must make sure those rabbits don’t come back.”

So she pursued the survivors to the edge of the woods, managing to slay two more before they hid themselves in the shadows. She stopped and caught her breath. There she heard the groan of an old man. It was too dark to see well but she thought she saw a burly figure resting against a tree trunk.

She called to him but he could not speak. She helped him to his feet, wrapped his arm around her shoulder, and guided him back to her cottage. By the time they returned the stars were shining in full array.

They went inside and Marrareth laid the suffering man on a bench by the table. She lit a fire, heated water, and warmed a roll of bread. When she brought the food to the old man she at last saw his elderly face in the fire’s glow.

He was one of the half-whorven.

His arms and face were more hairy than any healthy man’s ever were. His shoulders swelled. His teeth were sharp. He was ugly to look at but stronger than anyone Marrareth had ever seen.

She wondered if she should ring the bell. She wondered if she should send for a priest or just grab a poker and put the man out of his misery then and there. But she decided to wait and see what condition he was in when he awoke. When he smelled the bread he rose up sharp and quick and scarfed the bread roll down.

“Thank you,” he said. “Please do not be afraid. I am of sound mind now. Borister is my name. For some months I have lived in the woods by the Whispering Weir and spent my days hunting beasts. I have kept my distance for fear of what you would think. I wished to spend my last days serving the good men of the city so that when I at last die the gods should look kindly on me.”

“I am Marrareth,” she said. “Tell me, Borister, since no one so afflicted ever lives to be an old man, how long have you been like this?”

“Sixty years,” he answered. “I was like this from the moment of my birth. But never in my life have I tasted meat. Through prayer and through willpower and through only eating grass I have staved off complete madness. You did well to offer me hot water and bread or else I might have eaten you.”

Marrareth said, “You have a poor diet for someone who does such a good work. Stay with me. I will give you honeyed quinces and mushrooms fried in groundnut oil. In return I will hide you in the bell tower and you can help me clear the land and tend to the crops.”

“You are a kind woman,” said old Borister. “Thank you. I will stay and work for you.”

So for two weeks Borister pulled a plough and hauled buckets of water. He weeded, built walls, planted fruit trees, and fended off the worst of the forest’s monsters.

One day Marrareth’s distant neighbour the widow Annesse came calling and Marrareth had to hide Borister in the bell tower. Annesse brought some gifts with her including a jar of rendered pig fat which Marrareth was happy to accept. Annesse looked over Marrareth’s lands and marvelled at how productive they were.

“You must not work yourself too hard, Marrareth,” said Annesse. “Are you short on money? You know you can ask me, my dear.”

Marrareth said, “No, I’ve just felt very fulfilled in my labours lately. Worry not for me, Aunt Annesse.”

They moved indoors. Some time into their visit they heard groaning from the bell tower. Borister was growing restless in his sleep.

“Goodness me!” said Annesse. “Marrareth, it sounds like there’s a monster snoring in the bell tower!”

“No, Annesse,” said Marrareth. “The door is unlatched and swings in the wind. In fact I should go repair it this minute. Rest here a while.”

Marrareth left the cottage and went outside to the bell tower. She hoped to wake Borister so that he would not snore or groan. Annesse meanwhile was worried over her distant neighbour. Perhaps this was a poor time for a visit, she thought. She thought it would be kind if she left a hot pan of fried mushrooms for Marrareth to find when she finished her work, so she took some of the pig fat she brought, fried up some mushrooms, covered them in a dish, left a kind note, and went on her way.

After Marrareth had awoken Borister and brought him to his senses she returned and found Annesse gone. Wishing to give her dear neighbour a proper farewell, she headed out after her. At the same time, Borister came into the cottage and found a dish of his new favourite food – fried mushrooms. He could not have known that they were not fried in groundnut oil but in fat from a pig.

Marrareth caught up with Annesse and gave her a proper farewell. Then she returned to the cottage and found a disturbing sight. The door was torn from its hinges. The kitchen was a mess. In the fields, crops were trampled and trees knocked down in a wide path all the way to the weald. And of course Borister was gone.

She soon figured out what happened. Borister had eaten fat from a pig and at last lost his mind. She sighed, repaired the door, and cleaned up her kitchen. The next day there would be much work to do repairing what the whorven man had destroyed. Before going to bed she drafted a quick letter to the city aldermen asking if they had found anyone to send to help her.

Marrareth and Young Lady Niela Allarmaal

In a lonely land by the Whispering Weir lived Marrareth. She lived in a small dark cottage by a tall dark tower, and up the tower was a bell which she was to ring if ever weald-wights or woodwoses overran the Whispering Weir. She lived there alone, farming the fields and watching the woods and always hoping for a helper to come and lighten her lonely labours.

Tending these vital lands was a task that could be entrusted only to the most dutiful and trustworthy citizens of the city. Outlaws and truants were not to be trusted with this charge but sometimes unruly souls were sent to serve the land’s assigned guardians as punishment.

Such was the case with Niela who arrived at Marrareth’s door one day with a note written by her parents and stamped with the seal of the city’s aldermen.

To the Marchman Marrereth of the Whispering Weir.

From Lord Richly Allarmaal of the First Borough.

Miss Marrareth, we hear that you are in need of assistance in your post in the north. For neglect of her education and disregard for her manners, we are pleased to offer our daughter Niela, fourteen years of age, to serve you until her unbecoming tendencies are corrected! You are free to order her and discipline her as you see fit but I must forbid that any lasting bodily harm come to her. It would be improper to mar one of noble blood.

We will write you again and expect to hear reports of her progress.

Marrareth was delighted that the aldermen had finally found a helper for her. She immediately took Niela to learn the lay of the land. She showed the young lady the fields, the river, the weir itself, and the forge at the back of the cottage. Of course she explained how the bell was to be rung if ever weald-wights attacked them in force. Niela said nothing as all this was taught to her. Marrareth assumed the girl to be tired or shy. She expected a change of heart to come in the morning.

But when morning came Niela refused to do any work.

Marrareth took her to the quince trees and said, “Look carefully. This is how you prune. The location and angle of the cuts are both important. Now you try.”

Niela refused to even touch the sheers.

Marrareth pushed her to the nettle patches and said, “Look carefully. This is how you tell the weeds apart from the nettles. You must grasp them as deep as you can to pull out all the roots. Now you do it.”

Niela refused to kneel down on the ground.

Marrareth dragged her to the eaves of the woods and shouted, “Pay attention! This is how you slay a whorven shrew! You strike them on the head but don’t cut them or else their blood will taint the ground! Do it now!”

Niela refused to even look at the trapped shrew.

Marrareth tried punishing her. She tried withholding Niela’s supper. She tried making Niela sleep outside. She tried refusing to wash the girl’s clothes and making her wear an old cloth sack. Nothing would convince the proud girl to obey. Marrareth wrote to the aldermen time and time again begging them to take this lazy girl back who was now more a burden than a help.

But they refused to take her back. They wrote and said, “Not until her attitude is fixed.”

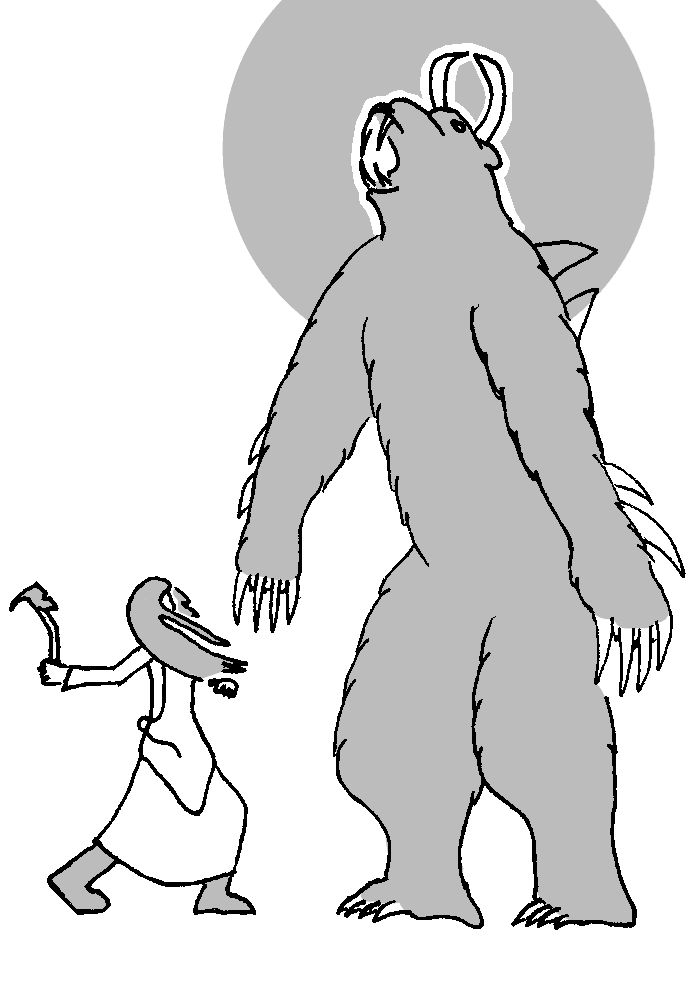

Marrareth suffered the lazy girl for a month with no change. Then one day something terrible happened. Of all creatures born of this earth, none are more terrifying than the whorven bear. Their teeth grow long as spears and their claws heavier than millstones. Not twelve champions can kill a whorven bear and one had just come bursting out from the woods looking for a meal.

Marrareth and Niela were out by the quince trees when it came. Dread and horror filled Niela’s heart as she looked into the beast’s eyes. She was inches from the bear’s teeth when Marrareth pulled her out of the way.

Marrareth then ordered, “Niela, run and ring the bell!” And for the first time Niela obeyed.

Marrareth fought the bear for hours while the two waited for knights to arrive from the nearest hamlet. By the time they arrived, the bear was growing tired and Marrareth was badly injured. The knights managed to put the tired bear down and Marrareth fell exhausted.

It would be a few weeks before Marrareth would heal enough to work again. When she was laid in bed the knights said, “What do we do? Someone still has to tend to this land. There’s no one to do it but us and we know nothing of farming or guarding the edge of the weald.”

Niela proudly told them, “Follow me! I’ll show you!”

She then showed the knights how to properly prune a tree and they were impressed. She showed them how to tell weeds apart from nettles and how to pull them from the roots and they were very impressed. She showed them how to properly kill a whorven shrew and they were amazed by her wisdom. The land thrived as Marrareth recovered.

When Marrereth was mostly healed the knights left. She and Niela carried on alone for a few leisurely days more. Niela at last had found the motivation to work and Marrareth had just begun enjoying her company when Niela received summons to return home. She promptly headed back to the city.

Marrareth tried to change Lord Allarmaal’s mind and wrote to him, “My Lord, I regret that I have not been able to do more to help your daughter. Please send her back and allow me to teach her a little longer.”

But Lord Allarmaal wrote back and said, “Miss Marrareth, I cannot express how grateful I am for what you’ve done for Niela. I never imagined she could become such a wise and hard-working young lady. I could not possibly burden you by asking you to teach her any more.”

And so it was that Marrareth had to carry on in the lonely land by herself. After she received the reply she still had a long day of pruning and weeding to do even as her wounds still ached. When she retired for the day she wrote another letter to the city alderman asking if they had found anyone else to send to help her.

So, Arturo, these are the labours of Marrareth which give many of us so much delight. Other tales do more to illustrate the woman’s selfishness which I suppose facilitates laughing at her trouble. More recent entries in the cycle have tried to justify her vices and place more blame at the feet of the aldermen. I understand why people do this but it undercuts the intended humour.

Please tell me how your friends and family receive these stories. I will enclose the lyrics to one of our popular songs on the subject for them to comment on as well.

Eagerly awaiting your next correspondence,

Alas for Poor Marrareth (To the tune of O Olf,)

Alas for poor Marrareth. Lonely she tills

The field she was given and guards the north hills.

Alas for poor Marrereth, lone on her land.

Will nobody join her or lend her a hand?

But look! The young knight with his cleaver so clear

Comes clad with bright silver, with eyes full of cheer!

He drives away dragons and carries in crops,

He fixes the floorboards and tends to the flocks.

But praise him not too much or else it will grieve you –

They’ll call him away, and then he must leave you.

But look! A great beast-man with arms full of might

Comes wandering, lost from his faltering sight.

He bears away boulders and pulls a great plough,

But snarls and snivels and snorts like a sow.

Now mind how he eats and mind how he feasts – he

Must never touch meat lest he turn the more beastly.

But look! A fair wastrel in dearest-bought cloth

Comes here a punishment, banished for sloth.

She faints in the furrows and dozes in ditches.

She rues her unrest – what a strain to have riches!

But send her away and right soon you will clean this –

She watched all your works and is now called a genius.

Alas for poor Marrareth. Lonely she tills

The field she was given and guards the north hills.

Alas for poor Marrareth, lone on her land.

Will nobody join her or lend her a hand?

Leave a comment